Anyone lucky enough to have a drink with me is aware of how much I love to talk about Cabaret. I am thankful to have lovely friends who are willing to oblige my passionate tipsy ramblings on the almost 60-year-old musical. Thanks to Eddie Redmayne’s performance on the Tony Awards, my typically-niche drinking topic is now the internet’s new favorite thing to argue about. So, I’m giving my friends a break on this one, and sharing my thoughts here instead. In short: this is my moment.

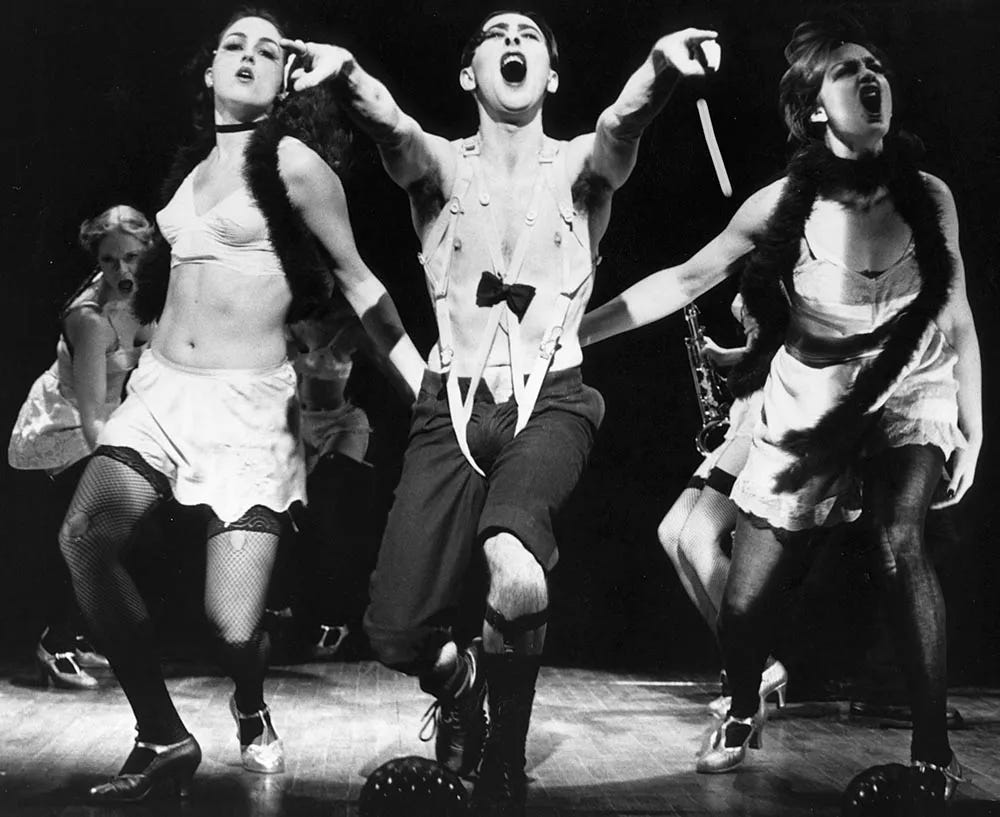

Cabaret is a musical based on the play I Am a Camera by John Van Druten which is an adaptation of Christopher Isherwood’s autobiographical novel Goodbye to Berlin. The show opened on Broadway in 1966 with music by John Kander, lyrics by Fred Ebb, and a book by Joe Masteroff. It was wildly successful; winning eight Tony awards (including Best New Musical), and ran for 3 years on Broadway. In 1972, Bob Fosse directed an Academy Award-winning film adaptation. Cabaret still holds the record for the most wins (8) without winning Best Picture—it lost to The Godfather. The show was first revived in 1987 by Hal Prince. That production was largely a remount of the original, but with a few small tweaks. Sam Mendes updated Cabaret with his revolutionary 1993 London revival at the Donmar Warehouse which transferred to Broadway in ‘98. That version was re-staged on Broadway in 2014, and 10-years later, we are back at the Kit Kat Club once more.

Director Rebecca Frecknall mounted a new revival of the show in London’s West End in 2021. The show opened to rave reviews and set a new record as the most award-winning revival in Olivier Award history. Frecknall’s "Cabaret at the Kit Kat Club,” transferred to Broadway in April, and the New York critics were not as impressed as their counterparts across the pond.

As tends to be the trend recently, any review the show received (other than a rave) was bound to spark backlash online. This criticism of the criticism turns into discourse and eventually becomes a snake eating its own brain-rotted tail. A phenomenon I suspect has everything to do with the current wave of anti-intellectualism/media illiteracy combined with the pressure to always have a hot take on social media. It irritated me to see very dumb interpretations of Cabaret passed off as deeply intelligent. It appears you can proclaim anything online and get away with it, so long as you tack on the following disclaimer: if you disagree with me, you probably just don’t understand.

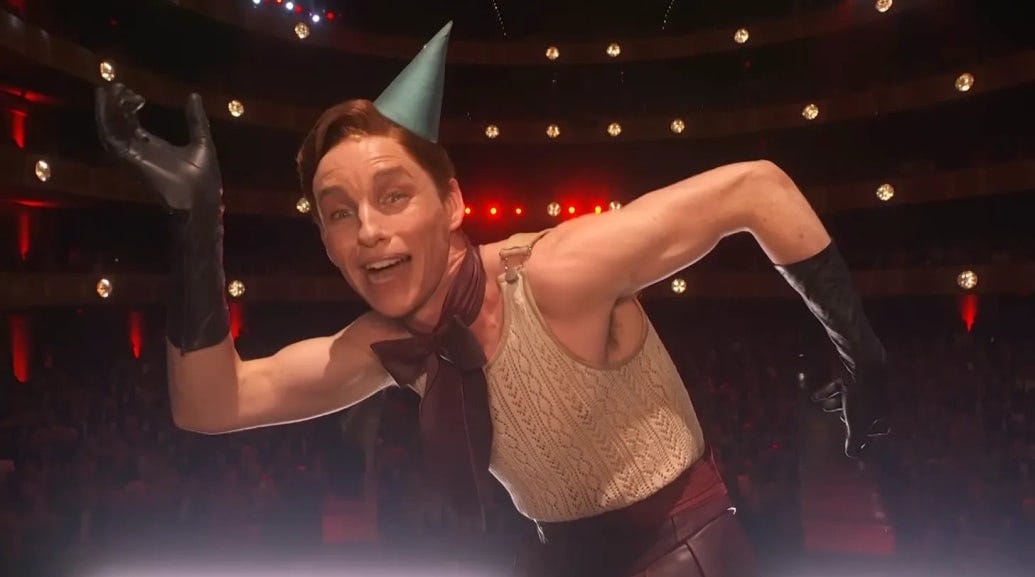

I thought I had made it through the worst of the Cabaret hot takes, but then the Tony Awards happened. Eddie Redmayne and his party hat soon filled my feed with a new crop of opinions. And you know what they say… if you can’t ignore ‘em, join ‘em. So here I am, giving my thoughts. I want to provide the disclaimer that I have not seen the revival yet (entering that ticket lottery daily!!), but I’ve seen the movie, the Mendes revival’s proshot, and read the reviews of the new production. I want to focus on the show and the Emcee more generally (we will still get to Eddie Redmayne don’t worry), because it’s the misinterpretation of the material that has been bothering me. Am I just another snake? Maybe. Like all the other critics of criticism, I think I’m correct. And, you know, if you don’t agree with me…maybe you just don’t understand the show.

Specific details change with each production, but the basic premise of Cabaret remains the same each time. The story revolves around the Kit Kat Club, a seedy nightclub in Weimar-era Berlin, as the country’s political climate starts to change with the creeping rise of the Nazi Party. Audiences watch the individual drama of the characters’ lives play out onstage, all of which is underscored by a simmering and ever-growing threat bubbling up right outside the walls of the club. In my opinion, Cabaret is a masterpiece; one that remains just as urgently relevant as it was in 1966.

The musical’s story is rooted in a specific moment in history, but has always directed its gaze back at the modern audience watching. Cabaret’s original director/producer, Harold Prince, wanted to show audiences the parallel between Germany’s past and the ongoing struggle for civil-rights happening in the southern United States at the time. He often retold this story when speaking about the genesis of Cabaret:

The first day of rehearsal of that show, I presented to the company a photograph from the centerfold of LIFE magazine and it was of these guys, white guys with blonde hair and crosses, naked to the waist, snarling and I said, ‘Where was this picture taken?’ Well the obvious answer is Nazi Germany. Well it wasn’t. It was Little Rock, Arkansas, and they were snarling at a little black girl who was going to a white school. My point was it can happen anywhere that human beings live.

It can happen anywhere, and it can happen here. That is important, remember that.

The show serves as a mirror; a metaphor made tangible by the original production’s set design. On stage, a large warped mirror reflected the audience back at themselves. Audiences watching the show in 1966 not only saw the parallels to current day, but being only 20 years out from WWII—were well aware of the inevitable consequences that came from that rising hatred. So, they watched the character’s indifference with horrified hindsight, and once the final song was finished, were forced to stare at their own reflections. The unnerving effect recalls the question posed earlier in the show: When faced with this reality, what would you do?

The physical mirror has been absent from subsequent productions, but Fosse included an homage to it in the film. Both the opening and closing shots are of a warped mirror reflecting the patrons of the Kit Kat Club. When Sam Mendes revived the show, he went a step further by involving the audience rather than reflecting them. Seated at small cabaret tables, they weren’t watching a club onstage; they were in the club. Frecknall’s new production further expands on this; the immersion starts as soon as you arrive at the theater, which has been fully renovated and temporarily renamed The Kit Kat Club. By destroying the fourth wall, the audience who used to be innocent observers are now the complicit crowd the Emcee plays to.

As an audience member, you are just like Clifford Bradshaw (the young American writer and Isherwood stand-in). He’s arriving to Berlin for the first time; ready to observe the scene there—a camera with the shutter open. He visits the Kit Kat Club on his first night in town, and finds himself charmed by Sally Bowles. Captivated by the fun and freedom of the city, he stops being a mere observer almost instantly. He doesn’t really notice this change until he realizes that he has unknowingly helped the Nazis.

The Emcee exists somewhere between the characters and the audience, linking us to the world of the Kit Kat Club. Though he is technically onstage in 1929, he is speaking directly to the modern audience. His musical numbers are a winking meta-commentary on the action happening outside the club, and are a silly and light reprieve to the ever-growing tension in the book scenes. As the Emcee says, “leave your troubles outside! In here, life is beautiful.”

In the second act, the Emcee sings the song “If You Could See Her Through My Eyes” while dancing around the stage with a gorilla in a dress. He laments that he loves her despite other people’s judgements. If they could only see the gorilla through his eyes, they would understand. The number is a campy and fun parody of the ridiculous views of bigots. Until suddenly—it’s not that at all. The Emcee changes the last line of the song. Leaning towards the audience, he dramatically stage-whispers a gut punch “if you could see her thought my eyes, she wouldn’t look Jewish at all.” He giggles and scurries off the stage as the audience realizes, horrified, that the entire song was one big anti-Semitic joke. A joke that they had just spent the last three minutes laughing at. The Emcee has betrayed the audience and made them unknowably complicit; just like Ernest Lugwig did to Cliff. Suddenly, your friend and guide to Berlin is not who you thought they were.

In order for this moment to have its impact, it is imperative that the Emcee gets the audience on his side. You need to feel lulled into believing his claim that there are no troubles in the club. He’s got catch you off guard; to get you laughing at his jokes before you know exactly what you are laughing at. If done correctly, when he turns on you, it makes you sick; even if you’ve seen the show a million times. His betrayal drives home the point of the show: it can happen anywhere.

Joel, Alan, and Eddie: Who is the Emcee?

Because the Emcee is such a blank slate, each actor has a lot of freedom to shape the role. Joel Grey’s original script had 5 songs, no lines, and almost no character description, so he had to invent this character from nothing. In his memoir, he wrote that he struggled until he remembered a comic he’d seen perform when he was a kid. He describes the guy as a total hack; desperate for the audience’s affection and willing to tell every cheap and offensive joke to get it. It wasn’t the outrageousness of the act that unnerved a young Joel Grey, but the fact that it had worked—the audience loved him. Grey decided to try channeling him, and the character clicked into place.

During an early scene in the film, a lone Nazi collecting donations is kicked out of the club. By the end, men in red armbands make up a majority of the crowd. If the Emcee is willing to do anything to win over the audience, his material will have to change along with it. He’ll do anything for laughter and applause; even if that means making jokes at the expense of his own identity (Joel Grey interpreted the Emcee as secretly Jewish and Alan Cumming’s Emcee is explicitly Jewish and Queer).

Recently, i’ve seen the Emcee described as “the soul of Berlin” because of the way he changes throughout the show. My interpretation is that he isn’t changing, only his act is. We don’t know who the Emcee is because we only see his onstage performances. There is an argument to be made that he, too, acts as a mirror by reflecting the changing attitudes of his audience. I think he is simply trying to appeal to the changing crowd. He’s not just accommodating the Nazis in the crowd because he loves the applause, but for his own safety as well. When asked about the character in a recent interview, Joel Grey described him as a a “soulless victim trying to hold on and hide that he’s Jewish,” and about his motivations, said, “I think he’s just trying his best.”

The audience sees the consequences of that futile effort when watching Alan Cumming’s Emcee. I think that is one of the reasons his interpretation is so compelling (aside from Alan’s obvious charisma). There is a tragic lesson to be learned from his Emcee: appealing to your oppressor will not save you in the end.

Eddie Redmayne is taking a different approach to the character. In interviews, he has stated that he’s not sure that the Emcee really exists; maybe he’s only a figment of the imagination. Or, that the entire musical has been conjured by him. It’s unclear to me exactly what he means by this. Is the show is just a story the Emcee is telling or did he somehow orchestrate everything that happens? Redmayne sees the character as a shapeshifter, someone who can run the Kit Kat Club, but once fascism takes over, easily conforms to survive. This rendering of the Emcee feels both simplistic and convoluted, and I think it’s indicative of the problem critics had with the revival as a whole: It’s trying so hard, that it’s missing the point. The flash is obfuscating the meaning.

Since I’ve only seen a truncated version of the opening number on the Tony telecast, I don’t know where he takes the character, or if the performance works on the audience. Is he charming enough to win you over in the beginning? I’m not sure, and that is a problem because it creates distance between the audience and the real-life threat. They went into the show assuming that (unlike the show’s characters) they would be able to tell the good guys from the bad because we all like to think this. Audience members suspect they are smarter than Cliff (because he ignored some of Ludwig’s sketchiness), only to be blindsided in the exact same way by the Emcee. Watching that Tony performance, I doubt anyone is shocked when that creep tries to trick them.

I keep thinking about this too: If you shapeshift from a strange inhuman marionette to the poster boy for Nazi beauty standards, do you run the risk of audiences taking away the wrong message? Is it possible that they can misinterpret that as the character becoming more human as he becomes the fascist ideal? Again—I haven’t gotten to see the full performance yet, so this might not be an issue.

There is a reason we find the Emcee so unsettling. It’s subtle, and can be hard to articulate because other than some crude jokes, he doesn’t do anything evil. I think part of it is how deceptively unknowable he is. Even as a child, Joel Grey could sense that someone willing to say anything for attention—and how successfully that works—is scary. It’s also incredibly relevant, and (if done effectively) could be a poignant modern-day mirror reflecting our attention economy back at us. Have you been sitting back and allowing dangerous ideas to spread because you would rather be distracted? What exactly were you cheering for when you laughed at that attention monger in clown makeup?

Hal Prince wanted audiences to walk away with a message, “it can happen anywhere that human beings live.” People did this to other people, and it was possible because other people stood by and let it happen. Not maniacal shapeshifters, not figments of imagination, but humans. That is what makes it so horrifying. Cabaret is supposed to be a wake-up call. Trying to forget your troubles and leave them outside will not work. Take a look at the world reflected in the mirror: life is not a Cabaret, old chum. So, what will you do?

Loved reading this. I didn’t know much about cabaret going into this but now it’s piqued my interest

I was waiting with baited breath for this and you didn't disappoint!! So so many people trying to defend Redmayne's performance by saying "the Emcee is supposed to be creepy!" No, he's supposed to be charming. As you said, what makes the show effective is the realization of what you've been enjoying. It's very difficult to do that if the audience feels disconnected from the Emcee right away. I haven't seen the show either, but I agree with you that it doesn't really seem like Eddie Redmayne understands what his job as the Emcee is which obviously distorts the message of the show. It's too bad, since Cabaret feels especially prescient in the US in 2024.

(I too have been known to drunkenly ramble about midcentury musicals. Don't get me started on the genius of "The Miller's Son" from A Little Night Music.)